World Window

Introduction

For our study, we would like to explore how users interact with our application and test the application’s usability. Our application is intended to help elderly people connect more easily and often with their families by allowing them to view digital photos personal to them, whenever they want. The guiding principle behind the design of our application is the adoption of a book metaphor: the interface resembles that of a physical photo album that can be manipulated by gestures resembling those used in real life. We interviewed several elderly residents regarding their feelings toward computers, and found out that they feel alienated by technology because it is unfamiliar, hard to use and above all too small and detailed. Our hope is that the skeuomorphic design of our application will help them recall their own personal photo albums so they can easily use the application and flip through our virtual one.

The driving question for the study is to discover if this book metaphor works. Our goal is to find out if WorldWall is an intuitive and easy way for elderly people to browse digital photos and feel connected to their families.

Methods

For our user tests, we recruited several senior citizens who are currently residents at Sunrise Senior Living in Palo Alto. We contacted the senior living community over the phone and conducted an initial meeting in person to chat with roughly 15 residents.

For our study, we briefly taught the users on how to use our application, by showing how certain gestures are used to navigate it. To test if these gestures are meaningful and easy to use, we had users complete tasks and gathering data on them.

We want to see if the gestures for opening and closing the book and turning the pages make sense. Users will run through three tasks total: opening the photo book, browsing different photos by turning the pages, and closing the book.

To determine the efficacy of the gestures, we can gather data on every attempted interaction, and particular on when the users used “incorrect” gestures or needed help and how long it took for them to complete a task.

We also tested the usability of our application. To do so, we timed how long the users spend just browsing the app, and at what point they became disinterested. We also checked for factors such as screen size and brightness, so timing when users become tired or experience eye strain was important.

After completing the tasks, we had a short qualitative survey for our residents. We asked them a series of questions regarding their feelings surrounding the application, whether or not they felt it was similar to a real photo album, and if they would feel more or less “connected” to their families.

Data we gathered

- General Information

- Name

- Age

- who they would use the WorldWall for (how many family/friends use Facebook, family/friends in general they’d like to keep in better touch with)

- How often they flip through their photo albums

- How often they receive new photos from their family members

- Usability

- Screen size

- Screen brightness

- Text/picture size

- Stand or sit?

- Desired distance away

- Gestures

- Page flipping: it’s accuracy/ease of use, do they like the interaction, have other preferences? Is it intuitive?

- How they swipe left/right? Do they swipe left to turn to a new page?

- Open/close book?

- If/when they get tired/disinterested

- Data on attempted gestures and results with particular focus on false positives and negatives.

Summary of Results and Discussion

Conversations

First, we arranged conversations with 14 seniors at Sunrise in Palo Alto. We introduced ourselves and had far reaching conversations with each of them. The seniors we met ranged in ages (one was over 100!), mobility and technology use.

Name |

Select Personal Information |

| Betty | Central Valley |

| Ina | |

| Lyda | Chicago |

| Ramac | Stanford Grad |

| Maggie | |

| Mill | UC Stanta Barbra |

| Siri | Finland |

| Liz | Seattle |

| Ruth | Salt Lake City, San Francisco |

| Brady | Palo Alto HS |

| Phillis | Suilisbery, Maryland, WWII |

| Barbra | Palo Alto, Stanford |

| George | Pennsylvania, England |

| Suzzie | Kansas City, Misouri |

| Lena | Centurian! |

We felt this initial stage was important to get to know our users better than we had during our initial observations. Beyond standard questions to discover user needs and technology use, we also solicited specific feedback on the direction of our product. At the time, while we noted how agile they appeared to be, we didn’t realize the importance of that data until further user testing.

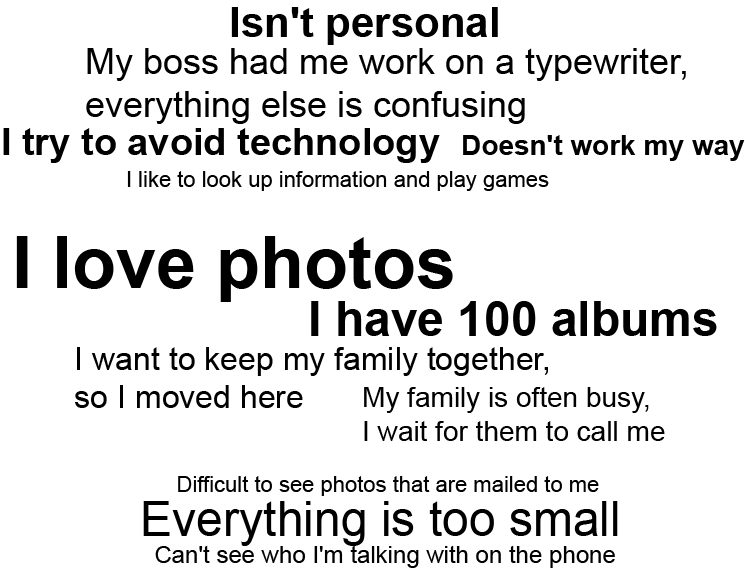

The data we collected and sentiment is representing in the sentence graph above. The most frequently heard sentiments on technology are the largest:

Prototype Testing

After this initial meeting, we returned for two more sessions armed with prototypes of our product.

The difficulty in designing for such a user group are significant. While our classmates might be more tolerant of Kinect errors and idiosyncrasies, most technology is already too frustrating for the elderly. In fact, we found that whenever one of their actions wasn’t registered, we’d frequently have to assure them that it wasn’t their fault at all and rather the software was to blame.

We also found that we needed to thoroughly explain why there was a screen in front of them and what it meant. When they understood the concept and were able to open the book, they immediately got the concept and we observed them smiling. But up until that point, our prototype was not successful in communicating its purpose and instructions for use without our intervention.

We also had significant issues with Kinect recognizing individuals sitting down and registering trigger events. First, the KinectJS ‘swipe’ event may seem natural to us, but turns out to require a very quick swipe in order to be registered. Thus, this automatically segments out some of the less agile users we had initially hoped to address.

We also had a couple tests with users where the KinetJS would not register any actions and interpret the user’s hand as being in random locations. While we didn’t realize it at the time, we realized at the end of our testing that this behavior was exclusive to users who had standing canes that they put next to their chairs. Our hypothesis is that these canes were recognizes as the person’s skeleton, which the Kinect would use to center their view. We need to figure out a way to make sure our users always have nearby access to their canes in the future, but that they don’t interfere with the Kinect sensing.

Ultimately, when the product did work correctly, the feedback was unilaterally positive. Once a user had swiped one page, they understood the model and reflected that it felt like they were looking at a personal photo album. Brief summaries of our data from six of the users we interviewed are below:

- Harvey Fetteuci: all negative (no response on the screen,) All false negatives. Kinect appeared to see harvey, but did not swipe hand fast enough. Got frustrated and felt he was at fault

- Jackie: All positives. Both right (4) and left (3) turns of the pages Screen needs to be bigger Thrilled to death.' 'So many people would use this'

- Paulene: From Bozeman, Montana All positives. 'This screen is used to me'

- Liz: All positives. Both right (4) and left (3) turns of pages. Uses a computer today to look up information, not communicate. Likes receiving photos, asked about sending.

- Barbra: Cane All false negatives. Kinect seemed to think Barbra was always on the far left of the screen, no matter what we did to recallibrate. Likes seeing the pictures. Likes that it's automatic.

- Lena: 100+ years old, cane. All false negatives. Wants pictures "I don't want email, I want to hear your voice"

Implications

Based on the results of our study, we believe that in the next iteration of our application, we could change or implement several things.

The swipe gesture used to navigate the pages of the book worked well, but as noted, required relatively fast arm movements that some residents were not able to perform. An area of to look into would be researching other gestures that would be easier to perform but also just intuitive to replace the swipe.

The observation we had about the cane throwing off the Kinect’s registering movements could also be explored further. An area to look into would be to see if there was someway where we could calibrate the application so that Kinect would not recognize the cane as part of the user’s skeleton.

Otherwise, our use of a digital book model was easy to digest by our users, especially after their first successful swipe.